or never and - Review - Peep

Review by Alice Fennessy for Art News Aotearoa No.204 Summer 2024.

Walking with Tohu - AAANZ Presentation

AAANZ Research Paper Presentation 2023

Dr Elliot Collins

This presentation is taken from my section in an upcoming Routledge Publication of Visual Arts Practice co-edited in Aotearoa New Zealand by Amanda Watson.

Because I have written this presentation in New Zealand I pepper te reo Māori throughout this talk, I’ll try to translate as I go or hopefully you can use some context clues to move the ideas along.

The Companion to Visual Art Practice provides an opportunity to bring together critical explorations of historical and contemporary visual art practice from within the practices of artists and makers. While there are numerous studies regularly published from the perspectives of curation, art history, and critical theory that examine art practices, these often result in art performing an illustrative role (e.g. to demonstrate concepts, theories, and political argumentation).

So this is an important collaboration by artists/researchers around the world. This writing is formed around one of six topics, Situations, Preparation, Im/materialities, Iteration, Collaboration, and Dissemination.

My practice and research most aligns with the topic of Preparation: to explore the conditions, influences, and practices that steer me towards art making. This section explicitly seeks to look to matters ‘prior to’ practice.

To begin at a place, this place, is possibly the only honest way to begin an examination of an art practice, based on memory in the landscape and the ‘creative compost’ that exists prior to making.

Monument to Wiremu Te Wheoro, Ngāruawāhia, 2017

This is a monument just outside the city boundary in a field, I am on the other side of the fence straining to read the inscription to remember Wiremu Te Wheoro. Memory is distant here and I’m uneasy wandering in a paddock. A townie like me doesn’t have a lot to do with cows.

So perhaps it’s better to take you a little closer to my home.

Tohu on Waitara Beach, before a storm, 2023,

I am alone on the beach, just before the rain, with our dog, named Tohu, who is searching or ‘researching’ for something dead to roll in. The work prior to making can rely on the other, in this case, a dog, to motivate movement and action.

The social and internal landscape of contemporary art practice occupied by a settler-colonial-linked artist is in a state of flux, trembled by indigenous languages and peoples and the inevitable power shift of reparations and volume control. There is a personal tussle every morning on the way to the studio or writing desk that occurs for all non-indigenous artists who toil in the fields of memory and place, in a place they do not belong. As an interconnected maker, feeling my way around, these shifts in language, power, and voice affect my practice.

Don’t worry, this will not be a quest for pity but for a path to walk, while I can. You will notice this kind of shift after your second pōwhiri, where the haukainga, don’t repeat in English what was just discussed perfectly well in te reo Māori. Or at the most recent Te Matatini, the kapahaka nationals, recently held in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, where te reo Māori was the first language and English came second, often preceded by a sympathetic eye roll. Not a brag, but I’ve been to France, India, and Italy and received the same indifference to English speaking but with less humility of understanding.

The power of language is just one example of this shift.

The work of one woke Pākehā, holds less assumed power than any other time in recorded art history. This privileged, almost singular perspective is crumbling and dissolving in its gradual decline and replaced by plural ‘knowledges’.

But what does this newfound softness of effect look like? How might it be used and applied to a reflective yet introspective practice? How might the preparations to a practice speak before the work has begun, and then echo within it upon its completion?

The precautions or prior actions taken in many different fields are often key to the next process’s success. Surgeons wash hands, bakers wait for dough to rise, a waiter polishes a wine glass or sets a table, and an academic reads around a topic taking notes and thinking thoughts. And all this they do quietly, without fanfare.

Quiet place and private time should be factored into this calculation of pre-making, I am here, alone, sitting and thinking in a small house, by a small beach, in a small corner of a small country, at a quiet corner of the world with the freedom to think and more importantly disagree with philosophies, theories, and political parties, making it a vital and nutrient-rich ground from which to practice. My contribution aims to celebrate that quiet time, or at least give it a voice.

Creative freedoms and critical thought that can be freely enacted in Aotearoa are also part of this preparation.

The privilege of freedom should be acknowledged on the way to the studio.

The current elements that will make up my section of writing are as follows; this is one of four main parts. The first part looks at the idea of being People From Far Away.

With three main Kaupapa,

The geography of practice is potentially the richest of places to think or make from. I will attempt not to stray too far into poetry or extended metaphor, as I do in my practice, but this space prior to making does lend itself to story that holds shifting truths and mailable facts.

In my mihi, I thanked Papatūānuku, Earth Mother and Ranginui, Sky Father, both of those names are poorly translated into English, yet both concepts are true and not true at the same time. The doublespeak that occurs in any colonized landscape is always a betrayal of someone else’s truth.

I’ve been thinking about this idea for a while since finishing my thesis in 2018. It’s the idea that Pākehā while connected to Māori via context are always living in a kind of very comfy exile. There is no real home to speak of, not like that of new immigrants, of Europe, The Americas, or the Pacific Islands. Or more importantly, tangata whenua, who themselves always have arrival stories embedded in their pepehā,

A pepehā is a sort of introduction and way of making connections, of closing the gap between us. So, they acknowledge distance, yet their whenua, their placenta, is literally placed in the land. There is a belonging for Māori that is secure and runs deep underground, while I skim the surface, without homesickness.

Ani Mikaere writes in Colonising Myths Māori Realities[1] that,

Pākehā people carry an enormous burden of guilt about the way in which they have come to occupy their present position of power and privilege. They also have a deep-rooted insecurity about the illegitimacy of the state that they have attempted to create on Māori land.

she continues,

Pākehā have developed a range of strategies to deal with these uncomfortable truths. One such strategy is the art of selective amnesia, which reveals itself in an apparent ability to conveniently forget vast chunks of history as and when it suits. Another is denial and distortion of the truth, for example, insisting that colonization was overwhelmingly a positive experience for Māori.

In 2021 National Party, a then opposition member of New Zealand Parliament received next to no support from his colleagues for his comment in a televised interview, where he stated that colonisation was, "on balance" a good thing for Māori because it led to the creation of New Zealand.[2] Sadly, This politician is now Minister for Treaty of Waitangi Settlements. Oh, he’s also the minister for Arts, Culture and Heritage, so I’m not thrilled.

The obsession with looking forward also typifies this stance, indicating a desperate fear of being confronted with the consequences of what has been done in the past.[3]

Again, I use New Zealand as my example, but with your recent referendum, you will understand that in a numbers game, the indigenous voice, in a colonized country, will always lose.

As an artist and researcher who works almost entirely looking in the rear-view mirror, walking backward into the future, this amnesia is not an option. Mary Modeen, in Decolonising Place-Based Arts Research writes, ‘what decolonizing requires us to do is to set aside the imposition or requirement that there is one government, one philosophy, one perception of the environment, one set of metrics, one belief system or worldview that has all the answers.’[4]

Looking back at the overwriting also means getting used to the discomfort of our forebears and the erasure or attempted erasure of names and language within the whenua. The better or more you can know of history, the better or more you can know of what is to come.

With subheadings like Being Everywhere All at Once, Performing Ritual on/in the Whenua, and The Compost of Art Making in Place, section two is concerned with making across place and time, and the ways in which a “Western” trained artist needs to move towards a more flexible understanding of spaces between time and between space, what in Samoan you would call the vā. This turn, crumbles hierarchies and linear systems of production.

This section is also about working with ideas of deep time, art time, dream time, and the way that time is needed to distill creative ideas before they are actioned. This is opposed to capitalist production which encourages you to finish that painting/product yesterday and sell the painting/product tomorrow.

Think of the global success of Hilma af Klint, work painted in secret and then stored, hidden away, only to be viewed twenty years after her death. Klint received visions that she made manifest in artworks, but she knew that their time had not yet come. Klint has used time to distill a body of work.

Or Katie Paterson’s practice, in particular Future Library which will see unpublished manuscripts written by well-known authors, housed in a special library called The Silent Room, that will be printed and read for the first time in the year 2114 on paper milled from 1000 trees planted in a Norwegian forest just outside of Oslo. You and I will be long dead before the work is realized and books printed, so will the authors and the artist. But the intent of this work is to commune or communicate across time to an unknown future from a dimly lit past. What my te reo Māori teachers calls ‘mokopuna thinking’ or grandchildren thinking.[5]

The third section lands heavily into the environment. And compares the two concepts of landscape and whenua. And the idea of the Western artist as tourist, remembering the value of the tourist to act as a reflective surface to those who have never left.

It’s important to know that in te reo Māori whenua is the word for land and ground is also the word for placenta. The whenua goes back to the whenua.

I’m investigating what place can mean, in different contexts, especially the way it influences a practice. Dale Turner in This is not a peace pipe, echoes renowned Māori leaders, Āpirana Ngata and Māui Pōmare, who argued that for any meaningful change to occur anywhere, both Western and Indigenous intellectual traditions must be respected.

Documentation of a tōtara log on Waitara Beach, 2023

As an example, there are stories of tipua or spiritual beings in Taranaki, where I live, that take the form of great logs, floating in the ocean, they come upstream or land on shore, to visit and watch over people in and around the beaches and rivers of the Taranaki coast, in the north island. This log, worn and ‘different looking’ from other plantation pine trees, after a big storm, came to rest on my usual beach walk. These knowledges, that do not belong to me, couldn’t help but influence how I interacted with this log, I stop to touch it often and while I’m shied to admit it, will usually address the log with a, “Tēnā koe e pā,” better to be safe than sorry. Not all taniwha are benevolent.

The unlearning that I’ve had to do prior to practice, and the un-then-relearning on the part of colonized indigenous peoples, around the world, can be seen in two examples of whenua views and landscape views. Indigenous artists are having to perform the double task in full view.

Lisa Reihana in her two 2015 works, in Pursuit of Venus [infected], and Tai Whetuki - House of Death, approach whenua in a very different way, populated with indigenous stories and peoples with in-depth and integrated ways of being in and being with whenua. A mauri, a living force exists within everything, in these works, everything seems to hum with presence.

While in Charles Heaphy’s work, ‘Mt Egmont from the southward’, 1840, watercolour on paper, the bucolic landscape painting of New Zealand is void of people and ready to be farmed, under a benevolent mountain by the sea. This tells a tidier, less complicated version of place. Especially for new immigrants to make a ‘Britain of the South Pacific’, without the hassle of having to concern themselves with those already here and the whakapapa or genealogical ties they had to every living thing.

And lastly, the fourth chapter deals with the notion of the flâneur along my local beach, a world away from a promenade up the Champs-Élysées, of the French bourgeoisie.

As a tutor at the country’s smallest polytechnic, it is a hard sell to funding bodies or parents with adult children still living at home, that wandering around, and being disaffected by society is an important part of the creative process, however,

I stand by it.

I mention Mātauranga Māori from over the fence. This highlights indigenous knowledges and the way they collide with Western mindsets of knowledge and knowing things.

Don’t get me wrong, I love the Māori world, I long to whakapapa to even the most tenuous thread of te ao Māori, I’ve even been folded into Ngāti Mutunga by marriage; graciously welcomed via marriage to participate in iwi kaupapa like working bees, inter-iwi sports events and Māori New Year celebrations. Yet I come up short again and again, watching from a distance the incredible progress made by Māori who had language, customs, land, and worldviews, among many other things, not lost, but stolen from them.

There is a trauma gap that opens up over lunchtime conversations. Kindly held close by all present.

Not to mention the troubling implication of Māori knowledges being taught by me, a non-Māori. There is an embarrassing, unresolved friction that will not be solved by my managers avoiding the Pākehā, the white elephant, in the room.

This section focuses on the problems of indigenous knowledges in the wrong hands. Or maybe not wrong but unqualified, colonized hands.

Barry, James, active 1818-1846. Barry, James : [The Rev Thomas Kendall and the Maori chiefs Hongi and Waikato]. Ref: G-618. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23241174

I like the depiction of two Rangatira in an oil painting by James Barry, 1820, it’s set in England and it’s Thomas Kendell, the missionary in charge, who looks the most uncomfortable. This is how I look whenever I’m unpacking Mātauranga Māori to my Māori learners and trying to share some whakaaro on different subjects in te ao Māori.

This last section also toys with the almost-arrival of art practice, trying to differentiate what and where the boundary of “real life” and studio life resides. Perhaps the line is too vague and shifty to be ever fully nailed down. Perhaps at the end of this chapter, I fail to define how time and space works in an art practice.

I hope, at this point, you’re not still wondering what this research or this presentation is for or about.

I’ll leave you with what, Kathleen Coessens, wrote in her 2009 manifesto called, The Artistic Turn,

The artwork does not reflect the long artistic process leading towards it. How, indeed, can the artistic outcome acknowledge these hidden dynamics? It cannot. This is the entry point, and the important role, for artistic research. Artistic research resides in the recording, expression and transmission of the artist’s research trajectory: his or her knowledge, wanderings, and doubts concerning exploration and experimentation. It is only through the artist that certain new insights into otherwise tacit and implicit knowledge can be gleaned and only through the artist/researcher remaining an artist while pursuing these insights, that he or she will be able to enrich the existing inquiries carried out by scientific researchers.[6]

In this sense perhaps, the studio lives in me, in all artists, and we’re always about to make something, always at the edge of creation, without relief, bound to this Sisyphean practice of making and unmaking, thinking, and doing, forgetting and remembering, preparing and failing, throwing a ball, continuously, only to have it returned, drool and sand covered.

[1] Mikaere, A., & Wānanga-o-Raukawa, T. (2011). Colonising Myths–Māori Realities: He Rukuruku Whakaaro. Huia Publishers and Te Wānanga o Raukawa.

[2] https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/444287/goldsmith-colonisation-comments-find-little-support-from-colleagues

[3] Ibid

[4] Modeen, M. (2021). Decolonising Place-Based Art Research. p.7

[5] In conversation with Maatakiri Rapira, September 2023

[6] Coessens, K., Crispin, D., & Douglas, A. (2010). The Artistic Turn: A Manifesto. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:191762281

Broken Monument / Empty Space

Pūkākā – Marslands hill

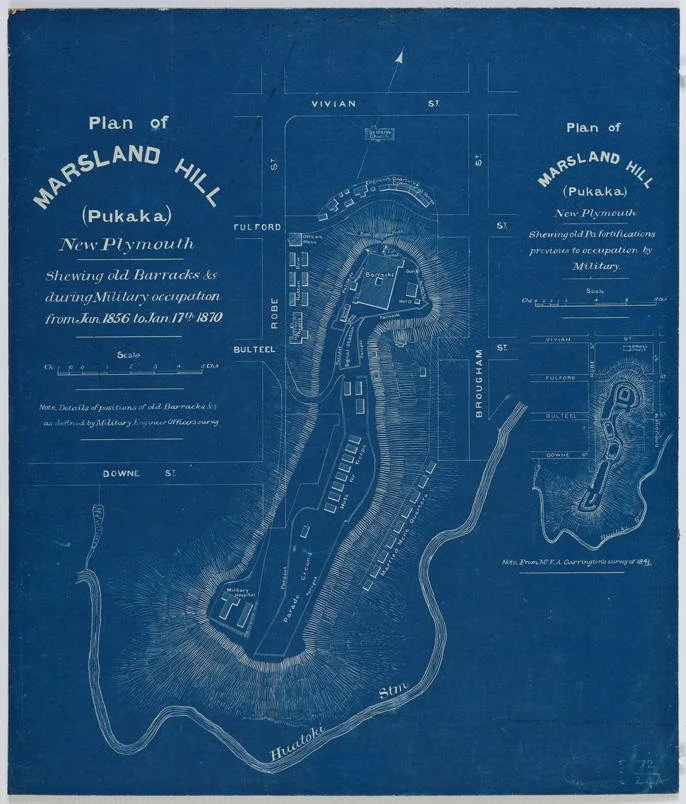

Plan of Marsland Hill (Pukaka)

Description

Blueprint copy of Marsland Hill (Pukaka), New Plymouth. Showing old Barracks etc. during Military occupation from Jan. 1856 to Jan. 17th 1870. Roadways are overlay the Barracks. Includes insert showing old Pa fortifications previous to military occupation. Note ' From Mr F A Carrington's survey of 1841'.

Date: Undated

Scale: 1 chain to 3/4 inch. 4 chains to 1 inch (insert)

Size: 65cm x 56.5cm

Lithographer: Unknown.

Accession number: ARC2005-395

Source: Puke Ariki

I follow the signs which face the wrong way in a Bed knobs and Broomsticks cold war kind of trickery but I know better, colonisation is always slippery. The new kind, I mean, the old colonisation was far more obvious, a gun or a beating, not words and policy.

Past a small business up a narrow drive is a carpark with a sort of non-committal dog walker and a tradie on a break, van door open to let the light breeze carry The Rock radio station noise into the distance. The star observatory sits oddly in the distance, always looking up.

It’s almost 11.30 and the day is sunny and the breeze is welcome, I walk over to a large sign that extols the usual Council-crafted public knowledge, making sure that all information is fair and equal and above all, “neutral”. Woven into the text is some underlying narrative that reinforces confiscation. Firstly, that Māori squabbled over this pā, continuing the “always disagreeing” narrative. Secondly, the New Zealand Company makes an appearance, I’m always fascinated that they use the New Zealand name but somehow are always forgiven their atrocities like distant relatives who we don’t invite to dinner anymore. Designated as a cemetery that failed to take, the hill does host one interred B grade celebrity of their time. The resting place of Charles Armitage Brown.

The grave was marked by a slab of stone taken from the beach. However, it was obscured when the top of the hill was flattened to allow for the construction of the barracks during the New Zealand Wars. The centenary of John Keats's death aroused interest in finding Brown's grave and it was successfully relocated in March 1921 and marked by a stone inscribed, "Charles Armitage Brown. The friend of Keats.” It’s hard to find much about Brown’s poem but the buried story of forbidden lovers lives somewhere under the earth.

No, I didn’t skip over the New Zealand Wars, this was the headquarters of the Imperial Regiment stationed at Taranaki. Plans to destroy and consume the land were birthed and dissected here. Later setter immigrants would begin their new lives here until 1880 until the site was levelled.

The view to Paritutu and the mounga as well as the surrounding rivers and coast and islands just offshore, is breath-taking, but there are objects in the way.

I don’t mean the small stone which, though diminutive stands proudly on the spot, just behind the newer larger sign. Repeating a truncated version of the history, a sort of visual representation of the little pieces of knowledge I would retain. This rock is set in concrete as all good plaque rocks are, and bejewelled with an unsympathetic Heritage Trails sign. Still, the lichen is growing nicely and it seems content and purposeful.

No, I mean the Carillion bells erected by George Kibby in memory of his wife Mabel. The 37 bells are held in the air by great concrete posts, little bell striking gadgets are attached to each. The patina on the bronze surface is coming along nicely, only a couple more decades before they cleaned and polished again. They are played at regular intervals throughout the day but I do wonder if no one is there to hear them, do they still sound out of place?

From the bells, I swing like Quasimodo, to a broken memorial to the men who fell in action or died during the ‘Maori Wars’ [sic]. I say broken for more than one reason, broken letters, broken language, broken Carrara marble, broken perspective but also there was a statue of a solider atop the monument when it was first made.

Lord Plunket unveiled the memorial at a ceremony on Marsland Hill on 7 May 1909. The weather was ‘far from perfect’. However, by ‘good chance, the rain held off until the Governor had got half-way through his speech. Then a slight shower fell’.[1]

Some 80 years later, on Waitangi Day 1991, the figure on top of the memorial was smashed by protesters. It was not replaced and the plinth remains empty.

Today there was just a shirtless man sitting on the bench, he notices me taking photos, and tells me with great certainty,

“that’s wrong!”

“What is?” I reply,

“loyal Maoris, they weren’t loyal, Maoris aren’t loyal”, [sic]

(I stare back for a little too long, lost in the confused, old-timey racism)

“What?” was all I could muster before he grabbed his bike and walked away.

I forget that many don’t see the heavy double meaning of a New Zealand Wars memorial in a country groaning towards a better future.

I enjoy this broken monument, for being just that, a symbol of something broken, a little wound on a quiet hill that just won’t heal. Fancy marble and pleasing proportions but mostly I like its incongruity with the landscape, the singularity of its lopsided history, and the stupid little wrought iron fence that keeps people from getting too close to history lest it rubs off.

There is another memorial, a fountain to the Anglo-Boer War which no one really knows about but it was basically white people (British) fighting other white people (Afrikaners) in 1899 – 1902 in South Africa. The memorial is a fountain that was moved downtown and then back up the hill again to make way for progress. Its base is now filled with a singular species of ice plant, fitting, as they’re endemic to South Africa. The middle tier still holds water and reflects the bright sun onto the underbelly of the curved upper dish, the breeze that still blows changes ripple reflections.

And before I leave to go and check out the now closed New Plymouth Prison, I notice a brutalist inspired, most uncomfortable looking concrete bench, with a simple plaque, my last hope of contemporary redemption. My hopes were sadly dashed. The plaque reads,

In Memory of

BERNARD FORD ARIS

1887 – 1977

The Painter of

Mount Egmont

God, will that name never die?

There is however an empty space on the other side of the bench. A small smoothed space, exactly the same size as that of Bernard’s, for a plaque to one day be added. I may have to make an early memorial plaque for myself and place it here, why should strangers be the only ones to enjoy my memory? My plaque will say,

In memory of

ELLIOT COLLINS

1983 - 2083

Who never painted

Taranaki Mounga

[1] https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/marsland-hill-nz-wars-memorial

Button Non-uments

These works are primarily based on time and memory, as well as movement through time and memory. It’s important to consider the foundations upon which the buttons are held as an important key. Driftwood is a strong metaphor, that idea that wood drifts is a really important aspect of the work but also that driftwood appears to be in a sort of purgatory or stasis, a liminal space, it's dead but not resting, it's moving and yet not attached to life, not growing. The buttons are also focusing on this idea of loss and movement across time as well. We lose buttons, we rely on buttons, they are nostalgic objects. It's a play on that nostalgia but also these objects as a whole form a kind of solastalgia, where they remain the same and the world around them changes. The colours are chosen arbitrarily yet they begin to speak of different attitudes, they sort of emerge within the work. I'm responding aesthetically and physically and visually to the construction of the work and where the buttons should go and I wanted them to be amorphous forms and to not be like the Australian artist Louise Weaver who creates animal forms, I wanted these sculptures to be memorials that could be moved, that could be changed, that hold significance and then be given back or could it be adjusted. These are non-uments, monuments that are recalling small things and small events. This works also set alongside other artworks, in conversation with them. They are drawn to them and whisper to them but they're also whole in themselves and can operate in solitude. Could they be a kind of non-religious votive? They hold a secret in a way that all good memorials do but yet are uninscribed like most. The eyes of the buttons always open like that of the tekoteko or portrait painting, following you around the room.

Friend, 2022, button on found wood.

St. Baz

St Baz

We interupt our normal programming to bring you breaking news of an unexplained occurence in downtown Auckland, we have Andrew McRae at the event.

Andrew can you tell us what’s happening?

Yes, kia ora Māni, I’m seeing what appears to be a supernatural event. A woman in her 30s is levitating about half a meter off the ground in the middle of Anzac ave.

She appeared to be crossing the street when she was caught up in what officials here are calling an ‘ascension’.

I’m sorry Andrew, can you confirm that for our listeners, you said this woman is levitating?

Yes, that is right. Little is known at the moment, about the individual in question, she is of Asian decent and I have been told that she works in the area. She appears not to be in any pain but we are unsure the reasons for such an event. I’ll bring you more updates as they are known.

-

That’s how it began. A normal Tuesday lunch time. The city rushing around as usual. But now with Yu-Jun Kim, suspended in catatonic extasy, holding up traffic on a busy road.

It was late February 2023 and ordinary people in New Zealand had reached a state of collective piety as a result of Covid 19 lockdown obediance and vaccination complience. But more than that, when asked to, they were kind.

We know this from interviews of these individuals who could explain very little about what occured during the ascension, but they all had the overwhelming message that goodness, kindness and caring for one another was the reason for the blessings.

The effected went into a state of indescribable bliss and all bodily function ceased seemingly, so there were no embarrassing mid-air “accidents”. Originally people were concerned and tried to help the early ascenders, but the Director General of Health reassured us that the medical check-ups during and after the first few ascensions, revealed that the health of the individuals in question were more than normal they were in fact, in perfect health. Some people argued the ascensions caused bone softening, though that was mostly misinformation disseminated by the newly formed but little known Anti-Ascension Forum or AAF.

Ascensions happened sporadically at first but became more and more common place. An inconvenience for employers but taken in their stride, especially since the blessing seemed to buoy people’s spirits and the national household spending habits increased every time there was an announcement of an ascension.

It crossed religious lines too, debunking early Christian rhetoric about the “correct” ‘path’ to follow.

There were no typical ascension times but since it seemed to be increasing a government app was eventually created to alert close family, friends, and allocated work contacts, and they could hold vigil. Though use of the app waned over time.

Miraculously, no harm would come to the ascended. These human vessels that were in communion with, what some were calling, a higher power, were protected from all external disturbances which some people attributed to the faint glow that came off the individuals, more easily seen at night.

Not that anyone knew, but the ascended were also tended to by the Anteortes[1] who are sort of protector angels. They ordinarily keep drunk people, stumbling home from the bar from walking into oncoming traffic. They invisibly jostle them home, making it to their doorstep with only minor bruises. They are the angels of near misses; not completely stopping accidents but making them less traumatic, stubbed toes, grazed knuckles, that sort of thing. They had a new assignment however, with the development of the Aotearoa ascensions.

There were of course the Phalums, the order of angels whose job it is to counteract the Anteortes good work, they spend most of their time fighting each other, that’s how the worst accidents happen, when the Anteorts are distracted in arm wrestles with the Phalums. But, for these rare moments of ascension, even the Phalums leave these carer angels alone, recognising the complete purity of each event.

The occasional house was robbed and those who lived alone with no contacts would often return to missing pets or shrivelled up vegetable gardens. But the elation, peace and enlightenment that followed the ascension was more than worth the loss of any trivial, stuff.

The evening news would announce the ascension like Covid numbers or severe weather warnings, or the way blossom flowerings are announced on Japanese news channels, with tags on the map marking locations of interest.

Each ascended was given an unofficial sainthood, not condoned by any faith group, as they couldn’t agree between themselves whose god was performing these miracles.

Yu-Jun Kim, the woman spoken of earlier, was one of the first ascenders, leaving her office in the customs brokerage building to grab lunch and rush back to her desk, she was crossing at the lights when the ascension began and there she was held in perfect benediction, for over 2 weeks. With Yu-Jun being the first it was considered a Buddhist manifestation, her closes link to religion was her Buddhist parents, however the family rarely went to pray and only really celebrated their ‘Korean-ness’ during occasions like the Korean New Year with her slightly disapproving parents in Glen Innes that their daughter was only kind of Buddhist to make them happy.

A few weeks later Dorothy Morrison of Blenheim was about to strike it rich on a bingo card when tables parted, chairs drew across patterned carpet and she hovered a meter above her Zimmer frame. There she stayed for 4 days 3 hours and 20 minutes. Suspended there with her bingo dabber, cap off, drying out in mid-air.

The episodes happened more and more frequently over the preceding months, and social services managed to get their heads around what was happening. Temporary financial benefits were put in place for the families of the effected loved ones. Emergency services were always called in case a temporary roadblock was needed and diversions for the general safety of the public though accidents in the areas of ascension decreased.

Rahul Mishra owns the dairy along Balmoral Road, down the road from the park. It was not an overly successful dairy, but it served his community, and he was lenient with school kids who stole day-old pies in the afternoons and came back the next day with only two dollars to say sorry.

He hadn’t been to temple in a while and thought himself not a very obedient Hindu. Life was busy, with only a few days away from the shop a month, a sleep-in was the most spiritual thing he could achieve especially with a wife studying nursing three kids under eleven.

However, after his ascension which lasted 6 days 17 hours, and 32 minutes he returned to earth and walked straight to temple with his wife and children who took time off school to be there when he descended.

Life returned to pretty much normal for Saint Rahul, his shop would be frequented by pilgrims leaving offerings of two dollars coins and flowers. Much like all the others who were blessed with ascension, his life became contented and calm, but he was much the same as before. The only thing that changed, and it was only he who noticed this blessing, was that the random bits of fruit he would have in a basket for sale would never rot while they were in the store. Staying perfectly just-before-ripeness, until they were sold.

Saint Beth of Taranaki. She was one of those good Christians, you know, the one’s non-Christians actually liked, not those who pretend to be nice and then judge everyone’s tithe amounts or gossip about their lockdown drinking habits. She planted trees and tried to learn te reo, she was better than she thought but St. Beth was hard on herself. Being held aloft for 17 days and 4 hours, St. Beth participated in what most think is the record duration for an ascension. It was in the supermarket, dry goods aisle and not on Sunday so removed the romance of being seen as a blessing to the church. After her ascension she carried on in much the same way as before, serving her small community. She did receive one blessing though, whenever she cooked for others which was more prophetic than most, the food would always be perfectly seasoned, even if she forgot to add the necessary salt and pepper.

There was the impressive occasion of a rather rotund member of parliament who ascended for 4 days 9 hours and 37 minutes, his heft was quite extraordinary suspended there in the debating chamber, right in the middle of question-and-answer time. There was media speculation and anger from the Opposition as some sort of stunt in an election year or unfair advantage but two weeks later a member of the opposition ascended for 4 days and 15 minutes which stopped the formation of a select committee to “root out spiritual favoritism within Government”. Both members post-ascension left politics entirely.

Uncle Tui, as he was called by everyone, caused a roadblock by the Taupiri urupa on the Waikato highway. He ascended while washing his hands after tidying the grave of his first wife. The mist came down to greet him and stayed the whole 12 days 3 hours and 46 minutes of his ascension. Since then, any house he visited noticed a reduction of dampness and the Waikato DHB saw a sharp decline in respiratory-related illness in the area.

Many elderly people ascended and that was easier to deal with but came as a shock to their adult children, who visited once a week, seeing their parents aloft in ecstasy only sometimes fully clothed.

The list went on and on to well over four hundred people. A nurse in Rangiora who after the event always found a vein. A farmer in Cheviot was able to talk to young farmers in the region, reducing suicide in the region with his incredible blessing of a kind manner and way of listening, a DOC worker on Raoul Island in the Kermadecs had lit a small fire on a still night, ascended and hovered above the flames for 9 days and 7 minutes. The fire stayed lit, but the wood didn’t burn. From that moment on his socks were always dry.

There we’re flourishes on the East Coast and that got ‘Māori Facebook’ chattering that Ngāti Porou had some spiritual superiority until similar Iwi ascension clusters occurred in Kaikohe, Whanganui and Hastings; at Parihaka it happened twice.

The Prime Minister reassured the country, with a stern furrowed brow that her government was trying to do all they can to find the cause of these unpredictable events but reminded reporters, who enquired on governmental negligence, that all follow-up interviews returned overwhelmingly positive responses.

This ascension season lasted a little over two years with the last recorded event being a man who would become known as Saint Baz of Tapu beach. His name was Bartholomew Wallace, a fitting name for a saint but not even his parents ever called him that. Saint Baz was in his Coromandel workshop fixing the neighbour’s lawnmower, stopping for a mid-morning cuppa, no sooner had he reclined in his favourite chair on the front deck overlooking the bay had the 9-day 12 hour and 40-minute ascension begun.

He was grateful for the attention, living alone since his wife had passed had been lonely for Baz, sometimes forgetting he was alone and making two cups of tea instead of just the one.

Someone made a small plaque for his gate and for the remainder of his years Saint Baz welcomed visitors to the front deck, told them different stories from his interesting and vibrant life with his wife.

The guests always thanked him and went on their way, fulfilled by sitting in the presence of St. Baz. And they always commented curiously that their cups of tea stayed hot till the very last sip.

[1] Pronounced: An-ti-orts

From my window

Published in HERE magazine, issue 7, 2021

Waitara flows with significance, as the flashpoint of the wars, but also and always as a humble river who named the town. It ebbs and flows from crystal clear to muddy brown depending on what’s happening up river, carrying stories from Taranaki mounga, who sometimes appears in the distance. The sucken-in township dosen’t boast of its beauty for fear of being found out. I’ve never lived by a river before, Auckland kept me somehow preoccupied with beaches and art galleries, bushwalks and long blacks.

The river out my window, is hidden from my view by ANZCO, a meat processing factory, but it pulses when the kahawai are running and hosts bombs off the bridge when the weather is hot. The people here are hard working and sincere yet seem worn down by the changing world beyond their borders. Or they’re tired of a world within their borders that hasn’t changed enough. 4am morning shifts take over from the 6pm nightshift, the carpark capacity rises and falls like the tide.

Manukorihi and Pukekohe pā appear above the town that bends towards the coast. During the weekends the locals lay down their tools, ‘round midday, and head to the edge of the world; always with fish ‘n’ chips and children in arms, speaking te reo, calling for caution and concealing all their H’s in effortless Taranaki mita. They make their way to the rivermouth where the two bodies of water meet, to be cleansed and renewed and whispered to by the wind, which sounds (somehow) different down here. It revives those who wander the shore and propell surfcasters into the sea. The wind slackens for those setting up bonfires as the stars emerge, children collect driftwood as the grownups discuss the week ahead not knowing what the future will hold.

Blog Post - for Asia New Zealand Foundation

https://www.asianz.org.nz/arts/reflections-of-varnasi/

How Knowledge Works - From Whakapapa to Wikipedia.

Bill Bryson asserts in his book Mother Tongue that ‘hello’ comes from Old English hál béo þu (‘Hale be thou’, or ‘whole be thou’, meaning a wish for good health) in the same way ‘goodbye’ is a contraction of ‘God be with you’.

Nowadays, hello is what we use when we feel to uncomfortable saying kia ora. Because blessing someone with life and wellness is just a bit to spiritual. It also means thank you, and sometimes goodbye? So confusing for my western mindset. But though I can’t understand how greetings work, I’m sure I can gather all the knowledge I want from kaumatua and Tohunga from historical documents and share it online, right? I’m a New Zealander.

All words have history, all have whakapapa or etymology and knowing this history forms understanding and understanding creates knowledge. It’s the knowledge part that myself and all (yes, speaking on behalf of all my people) pākehā stumble over and refuse to understand. If you don’t think words matter just mention white fragility around pākehā and watch them either wither and die or become enraged and fighty. I’ll get to visual and cultural appropriation another time, we gotta break these things down to their parts.

Here are some of my thoughts.

When reading and researching early arrival of pākehā and tauiwi to Aotearoa, I’ve had to read between the lines from even the oldest texts concerning missionaries and settlers as they try to glean knowledge from first recorded conversations with rangatira and expert orators. Once I began, I found that they were softly whispering on the page, that not everything is for everyone. They sort of doublespeak and they knew how to do it. They’d tell small portions and only in part, they keep talking about connections and referencing things in context with other things, overlapping and circling back to another story, they seemed to stop and start, beginning in the middle of the story or cutting short a description. They sprinkle morsels of wisdom within their knowledge that is imparted knowing all too well, even back then, that it would be adulterated by less illuminated minds, schooled in an English tradition with God at the centre of their worldview. A world where time and people and plants and animals are separated and in order, top to bottom in the great chain of being. It would later be used to sell books and trade land for less than fair exchange. It would be manipulated to turn the gospel into a fable that would appeal to a tribal people ‘like those of Israel’. Let’s hope the Māori don’t get their hands on the New Testament, spoiler alert. Their knowledge would be taken and recorded, often incorrectly, condemned to a page and so could die there, especially when they are no longer allowed to practice traditional customs and knowledge systems because of sweeping laws that continue to ripple out today. Only hunting birds with firearms, no traditional medicines, only one God, call him Io if you like but he’s singular and a HIM and forget the rest, no marking of bodies, as it’s a crime against god. Native birds, so treasured by all New Zealanders, now at the edge of extinction with no-take rules discouraging Māori from even taking notice of te taiao that once sustained their existence. The Māori mortality rate still at an anomalous distance from their pākehā counterparts, I have a theory based on the weight of bullshit that Māori have to carry around from birth due to racism and cultural bias that is weighted against them causes weariness to set in at an earlier age. I know know this is far from the truth and it’s more likely improper treatment and care for Māori at all stages of care liked to negative unconscious bias of doctors, nurses, healthcare workers, teachers and phamacists. All karakia are linked through with mentions of god in trees, water, oceans, wind. So, forget those karakia and practice the lord’s prayer, in te reo is fine. And tā moko, though making a resurgence, is still met with stares and disapproval and the occasional entitled, ‘well-meaning’ comment, but they had such a beautiful face (before).

But this post is about the loss of knowledge or giving it back, whatever is less painful.

Not about the Māori loss of knowledge or pain, I can’t speak to that, but of the end to pākehā having access to everything Māori and ending a kind of silent trauma. We’re gonna hate it and it’s gonna feel like a loss because we’ve had access to it for so long that it feels normal and to have it limited is gonna feel like loss.

I get it, because I come from the great lineage of idea gatherers, knowledge collectors, customs adopters, language mergers, land acquirers* (wink), people observers and profit makers. I was taught that everything can be yours, at a price or with enough hard work or perseverance. That the expectation of knowledge is free and available, to a mind that thinks it can carry the weight of generations. I read in old books and find online, knowledge that was shared in confidence yet used in the quest for greater dominance. I start to think that if there were other white men, who cared enough to enquire got the goods, then I somehow deserve even more of the share, because oh, I haven’t told you yet, but I’m a better pākehā than they were.

I’m really good at reading and I can find all sorts of connections to te ao Māori on Wikipedia.

But I’ve noticed something about this kind of thinking and reading and “knowing”. It’s always from the outside looking in. It’s not Know-ledge is Learn-Ledge, (that’s ugly, but you get the point I’m making). That’s because it costs me nothing to type in a word or open up an entire whakapapa line, to lay it out in the open and carelessly let it dry in the sun. To unpick whakatauki and use it to bolster my Instagram post. To stumble over pronunciation or sing waiata out of tune only hurts my ego and does not pull on the whakapapa ties that connect Māori to everything else in the universe.

I continue to read and learn and listen, but I’m quieter now, and humbled by what I have been given. But I’m working on the loss part, how do I describe the loss? It’s not a death, the knowledge is still alive, marae still gather, tangihanga continue with the utmost care. It’s more like having hunger pains but the tin of biscuits is in the other room on a high shelf. However, I’m in the kitchen and the fridge is full. That’s my best extended metaphor I can come up with.

There are doors, or jars, that will never be opened for me. Because they’re not for me.

So, when you’re next around your Māori mates or walk into a room where maybe a few of your Māori co-workers are talking and they suddenly grow silent it might not be because they think you’re a bad pākehā or not trustworthy, it’s just that they’ve got their entire ancestry resting on each of their shoulders and they need to keep a little bit back to help them bear the weight. Maybe they were talking about something a grandparent said or telling a story of what they just learnt when they went up the river or to the marae, went for a hīkoi or gathered some food with an aunty. Maybe you long to ask follow-up questions; but how do they prepare the karaka berries? Where is the best uku in the banks? How does that waiata go? What’s the best rēwana recipe?

You might feel left out, or that you’re on the outside of a club you’ve always wanted to be part of but maybe, but just for now, and only for the next 250 years, you can be a supporter and just put the jug on and ask if anyone wants a cup of tea. Keeping in mind the colonial project brought tea to the English colonies via the East India Company who used not-quite slaves of the lower caste in India, ugh, it never ends. But that’s another story.

*to be written about in another post.

We May Never Meet Again

We are delighted to start the 2019 exhibition programme with new work by Elliot Collins. This is his first exhibition in the gallery in three years and over that period, he has been busy with a, now completed, PhD exploring historical monuments and memorials in the New Zealand landscape and their relationship to memory and identity. His new multi-media exhibition extends his notion of "memory markers" from a primary association with death into a celebration of life. We may never meet again draws on notions of memory and momentary observations. It memorialises the small, often fleeting experiences or feelings, and exhorts us savour the moment. "I feel that these paintings can act as a salve for contemporary life, slowing and soothing," Dr Collins says. The exhibition comprises oil paintings on board, unique photographs and copper discs that all operate in different ways to create memorials that elevate the everyday. Ann Paulsen in an article in Art New Zealand Winter 2018 describes his artworks as "collections of sensory perceptions and knowledge, waiting to be activated by the viewer. These markers operate as 'open' texts, with the possibility of, the provocation to discover, multiple meanings." We are delighted also to launch a new billboard by Collins which reinforces the exhibition and plays with the multiple connotation of 'still' and the idea of bearing witness. Collins has exhibited nationally and internationally and has been the recipient of international artist residencies in France, The Netherlands and most recently India.

Wharekauri

A Memory of the River

Nathan Homestead, Manurewa, 11 August - 22 September 2018

If you stand at the door the room to your left is partitioned by a row of saree sourced from various market shops along Dashashwamedh Road. The video work called From Assi to Brahma, 2018, was all filmed through the Rolliflex camera sitting on the windowsill. This is an attempt to record the various ghats (steps) that follow the west bank on the River Ganges. I say attempt, because as a stranger in a strange land I can only ever know a place from a distance.

This show is the culmination of my time spent on an Asia New Zealand Foundation artist residency in Varanasi, India, and as a collection of work it is a retrospective of failure. Failure, in the best possible way. In the show I do not attempt to seek enlightenment or push it on others, nor do I use the common tourist trope of photographing the more “colourful” locals of the river, projecting a kind of human zoo onto the ancient city.

I show you my various attempts of capturing the un-capturable in trying to contain the vast depths of story and history through a camera lens or at the end of a paint brush. All are genuine attempts of record, but all fall short. The dust does not get in your eyes as you travel the streets and alleyways in the photographs. The paining does not capture the smell of places moved through and around, and the video does not portray the feel of hot, dry wind wrapping around everything it touches.

It is perhaps the kaleidoscope work, sitting on the seat and named after the philosopher, speaker and writer, which best describes the visual sensation of life in Varanasi. Every time I went to the river I would buy a new beaded necklace. Haggling the price down from 300 rupee to a more respectable price, later realizing, with the exchange rate checked, I was haggling over a few cents.

The painting A Memory of the River, 2018 was painted over two months and was added to daily. The dry heat evaporated the oil paint allowing for layers to be added more frequently without mixing with each other and so the colours, like that of the city, stand out against each other, fighting for attention while always moving in a blur.

The watercolours were inspired by the brightly painted steps of the ghats. Lines of unnatural colour reflected in the river and are covered with thick mud during monsoon season only to be wash off and intermittently repainted. I only used water from the sacred river to make these paintings hoping again that this would somehow impart a holy resonance to the abstracted lines. The lock in the small room is gold leafed and hangs, holding on, prayed over and blessed by the man who sold it to me. He said to gold leaf it for more blessings. I tried to tell him I was an artist, but he didn’t seem to care. The small stool covered with bindi dots bought from a stall; in a jewellery section in a market where I was too often lost in, responds to the absurdity of the place. The collision of faith and commerce, beauty and poverty and industry and subsistence living, it is a contradiction, sacred and profane but holding meaning and space all the same.

New Show with Martin Awa Clarke Langdon - Te reo Pākehā

Review of show: https://pantograph-punch.com/post/unmissables-july

Date Paintings

In 2012 upon entering England the border agent at customs check point was very firm, reminding me that I was only to stay in the island kingdom no longer than my 90 day holiday visa. Should I explain than both my parents paternal and maternal lines trace back to England and so I am from here? I decide to just agree and move forward into my hostile ancient home. I’m aware of how citizenship works, and genealogy is not it.

So, I am positioned back in Aotearoa. The only home I have known, having to embrace the feeling of being in exile. Māori have found a way to deal with this exile. They hold Hawaiki within their identity story. A placeless place that is over the great ocean of Kiwa. It is a beautiful and complex understanding of coming from one place but belonging in another.

I am, of course, envious. Hawaiki is a placeless place that the dead return to, it is real and not real at the same time, there is mystery there which is not to be unpacked or investigated by non-māori. England however, is a locatable place that I’m not even allowed to spend two seasons in. When I die my spirit goes nowhere. Or at least if it does it is not in any cultural story of whiteness I have found. Perhaps the best story I’ve heard is that your soul just moves to another suburb. So, in the Heideggerian sense, to focus on dasein, being-towards-death, I have realized that if England won’t have me and I’m to be a happy exile within the island paradise perhaps it is time to do away with British/Eurocentric time-thinking all together.

I’m not suggesting throwing the baby out with the bath water but maybe just a readjustment, to time and space. To really resolve this tricky identity thing ‘we’ (white skinned, non-Māori or European/British heritage) might begin when our story begins. Or place making and our place losing. The loss of England and Europe via emigration to a wholly new and strange place. To begin it is important is to realise that ‘we’ are not living within a singular narrative but are merely an easily sunburned addition to the original story of Aotearoa.

This has shown itself as a western overwriting of Māori from its beginning. Colonization was and is a large subplot to this story and it tends to drown out all other voices. But as part of owning a story of identity, a real story, these date painting began to consider the beginning of pākehā space and time from 6 October 1769. The sighting of New Zealand, I say New Zealand because that’s important to the prologue. I have begun a new calendar system that starts from that fateful day to establish a way of tracking pākehā presence.

TE TAU TUATAHI – A.C.

The first year, followed by the acronym A.C. which plays with B.C. / A.D. timelines, these could stand for After Cook, After Contact, After Collision or After Colonialism. The last title I am dubious to use, not because of its baggage, that should be addressed and made aware of on a daily basis, especially those who continue to benefit from its lingering imprint that seems to mark everything if you look deep enough.

I am uncomfortable with its use because colonialism continues, and it has not stopped since first collision so therefore cannot be referred to in the past tense. So far there has not been an after colonization in Aotearoa.

I mention the prologue because I have not used the sighting of New Zealand by Abel Tasman as the beginning. Mostly because he didn’t set foot on land. And his only encounter with Māori was a violent one. I am perhaps being naïve by trying to reset time in order to give pākehā a second chance at redeeming themselves and endearing themselves to tangata whenua. Spoiler alert, they didn’t. The dates in the show note 248 and 249 years since Cooks landing based upon the Māori calendar’s new year falling within the pākehā months of June and July.

I have used te reo māori because it is the first language. It seems only right to use the language that was the only language spoken right up until that moment of contact.

I have used Obelisk typeface designed by Alistair McCready to entrench the idea of carving and engraving of messages into solid objects so this ‘fictional’ time is locked into the world through the production of the paintings and the artist’s willingness to hold value in this way of recording a new time and new understanding of a pākehā or non-Māori position in time and space.

Māori _____ flags

These copper plates are the same size as the field notes taken by P Reveirs and William Francis Gordon of flags ‘captured’ or ‘confiscated’ by British militia during the New Zealand land wars. Their titles, taken from the Te Papa digital archives are etched into the surface and all forgo tohutō and all use the pejorative world 'rebel'. They are polished only once in their lives. After that, they must be handled without gloves by anyone moving, hanging or holding them. The copper will hold a mark when it is touched, the oils on your hands are a marker and will reinforce the idea that everything you do, all actions, all language, leaves a mark.

Everything you touch/contact is changed by your presence. Whether you realize it or not, unconscious or not it is changed by you.

Like digging up ancient monuments or ruins, these works recharge an understanding of cultural views during a formative time of the colonial nation as it stands today. The deceptive subtleties of language continues to elude discussion and clarity and therefore remain undisputed or unprocessed and therefore still retains negative power. Why are these not titled freedom flags or opposition flags or even flags of faith denominations? These works are designed to record the marks and touch of its human collaborators. It will not be cleaned, and the work will oxidize over time.

So maybe these works are just a note to the viewer and maker that whatever they touch, that thing is altered and reacts, it changes and is changed by your presence and the way you decide to give it language. It could be an environmental aspect, but this is more of an historical perspective. That my very presence in research is leaving a mark upon history and it is my responsibility to make sure I am confident and comfortable with my residue.

Home Again

I have only been home for a week or so and already the norms of life in Aotearoa have begun to creep back in. I do love it here, so I never fight the inevitable closing down of senses that occurs in your home surroundings, I enjoy the smaller world that drew me home, but I do find myself daydreaming of my time in Varanasi when a memory comes to mind, and I don’t fight that either.

It’s the everyday things of Varanasi that I have noticed lacking here like standing at fruit stands outside dairies I miss the fresh juniper berries piled high smelling earthy and sweet and at the same time savory and aromatic. Missing are the jackfruit and the guava or coconut, freshly cut to enjoy the cooling liquid inside. I miss the commotion of small shops selling only padlocks or prayer mats or metal kitchen ware. I carry on down an urban Auckland street trying to smell for the hot coals placed in the chambers of antique clothes irons, working on business shirts being crisply starched after their wash in the river. No one stops to offer you chai with its sweet and spicy sugary kiss. No one is hanging around chatting or passing comment on the world that passes by, it’s as if everybody is too busy here to care about observing ourselves.

On the main streets, in tuk tuks or on the boats of Banaras* men sing to themselves, many different songs that I will never learn, their voices surprisingly good and betray their weathered position in life; yet here, silence. No ringing bells, or honking of horns, no calling out to tourists, Indian and Western, “where you going!?”, “Where you from?!” “Youwantboat?!” in a single word. Their nuanced language always beginning with hello was reinforced with a smile and open hand. Broken English is the common tongue in the city of travelers and pilgrims in a country of 22 official languages and many more dialects to consider. It was always a joy to chat to school children with astounding English skills who always wanted selfies and to practice conversations and taxi drivers who knew no English and couldn’t read Hindi who would often drop you off in the opposite direction to where you wanted to be. Never in my life have I checked my privilege so regularly and been confronted with my own ignorance so frequently.

I miss the broken buildings being kind-of-repaired and wondering if the underlying structure was demolished or restored before being over built and painted over. Much of the city was destroyed and rebuilt throughout its volatile and dynamic past. There is something about the hazard of buildings in this place with its severe lack of health and safety regulations that reminded me of more honest times of personal responsibility that I’ve never lived through.

This captivated me but barely fazed the nonchalant young men and women of the city. They navigated the busy streets and narrow alleyways like fish in a stream, the young men with fresh haircuts and women with determined attitudes that have affected a drastic change in the community structure and power of women in contemporary Indian society. Their Royal Enfield motorcycles lining the streets as they participated in the abundant nightlife while they discussed the future of the city and country while also streaming a news channel on their smartphones. There is such a vast difference in wealth and income in the city that I could barely even brush the surface. But the growing middle class of India seems be embracing a western world view with their desire for all things western, clothes, style, food and technology which is quickly replacing ritual and customs and subduing identity. It was strange to be in a place that seemed to have nullified colonization so thoroughly be so easy swayed by western ideologies. As with anywhere I’ve travelled, people are aware of the way globalization creeps into the small sacred spaces of life and distorts it for its own purpose. Time will tell how Varanasi combats capitalism and greed in the Hindu city.

I had a conversation with a student from BHU** and he wouldn’t be convinced of how cool it was when Indian men wear all white Sherwani or Kurta for special occasions and temple responsibilities. He reminded me that (traditional) Indian clothes are from history books and western clothes are from television, he was 19 and I couldn’t convince him about the importance of the past nor should I, his future looked bright. Conversely, when I tried the sherwani on I looked like a disappointing substitute member of the Backstreet Boys (circa 2008) which he’d never heard of. Another astounding pastime that me and the other guests of Kriti Gallery artists in residence all played, was watching sari-draped women riding sidesaddle on the back of motorbikes as they wove through traffic and never once got snagged on the cities always loose wires, car parts, tree branches or other vehicles. The blur of coloured saris will stay with me as I return to Auckland’s drab fashion aesthetic of black on black with a hint of navy to add colour. I now long to see sadhus praying and reciting sacred texts or men in carts selling raisins or pomegranates in tidy piles. Auckland motorbikes seem boring now with only one passenger, don’t they know you can fit three or four people on one bike, you just have to hold on tighter.

I’ve since wandered along the Waikato, the regions own sacred river. But there was no one there. Some tourists stopped to use the public restrooms and granted it was a Tuesday but any day of the week the Ganges flows with souls, both living and dead. There is life to be lived down by the river. Maybe this is the sign of contemporary life in Aotearoa, where nobody has time to keep the river company maybe that’s why our rivers get sick or maybe this is why the river stays clean. The Ganges is one of the most polluted rivers in the world owed almost entirely to chemicals and pollutants from factories and agriculture as well as the cities struggling sewage treatment system which looked more like a Wes Anderson set piece than a functioning facility. This did not deter sons and daughters in their mid-fifties guiding their elderly parents to the water’s edge. I watched their cautious steps across the submerged stones just under the water where they appear for a moment to walk upon the surface of the oily sun licked ripples, and in this way every magical thing seemed ordinary. They bathed and washed away sin in the holy river that only a few meters away received the ashes of newly cremated bodies of the departed, all are blessed, all are made clean.

What I’ve missed most is the people, looking past the sales pitch, which wore off once they were convinced you were not interested in buying yet another necklace of prayer beads or brass pitcher. Once you got through that the people of Varanasi were really interested in what you were about, they were inquisitive and would stare without embarrassment at this bearded, European looking traveler with long hair tied in a knot, with arm tattoos, photographing broken steps and sleeping goats.

There is a warmth to the Indian way of being, avoiding harm and living simply, prayerful in greeting and grateful of exchange, yet sadly things are beginning to blur in my memory. Like I said, my real life is returning to me like waking from a dream. But you cannot return from India unchanged. It altered something in me, something that, like the place itself, is hard to describe. Under the umbrella of the Asia New Zealand Foundation I did not “discover myself” but maybe uncovered a part of myself in a place entirely new and exceptionally old and this is where the real richness of the program resides. The opportunity of an extended period of time held within the relative safety of the city and the residence was an experience that is hard to describe or fathom in this writing, but one that will be long lasting and slow to reveal its true impact. I swung from being overwhelmed and broken to being thoroughly at home and at peace, walking the small alleyways or dodging bikes on the main streets, holding quiet space in temples and laughing as a tuk tuk drivers tried, unsuccessfully, to double the price of a journey you’ve taken many times. I followed the path of pilgrims and sat drinking chai while vendors fixed a bicycle under a swastika sign. I encountered the profound and ordinary all in one place, outside of time and within ceremonies in temples, shop floors and doorways.

*Local/common name for Varanasi in the city

**Banaras Hindu University

Sarnath

I didn’t tell you about the monks! I’ve had the opportunity to go to Sarnath International Nyingma Institute. It’s a Buddhist institute that holds the sacred text of Buddha as well as teaching young Tibetan monks English while still carrying out their other scholarly duties. We planted some trees and last Friday we cooked them dinner as a graduation celebration. On the first occasion we got to witness the Stupa ceremony which was really special and on my return I saw the lid complete. A stupa (Sanskrit: "heap") is a mound-like or hemispherical structure containing relics (śarīra - typically the remains of Buddhist monks or nuns) that is used as a place of meditation. A related architectural term is a chaitya, which is a prayer hall or temple containing a stupa.

In Buddhism, circumambulation or pradakhshina has been an important ritual and devotional practice since the earliest times, and stupas always have a pradakhshina path around them.

This kind of stupa is known as the "Stupa of Many Gates". After reaching enlightenment, the Buddha taught his first students in a deer park near Sarnath. The series of doors on each side of the steps represents the first teachings: the Four Noble Truths, the Six Pāramitās, the Noble Eightfold Path and the Twelve Nidānas.

What Gold Smells Like, a recap.

Here are my latest thoughts. This entry is a recap of my residency so far for the Asia New Zealand Foundation.

It seems strange to talk about being half way into my Varanasi residency, but my half way point is approaching and it feel apt to mention navigation, space and perspective. This place walks the fine line of truth and fiction. It is easy to see how mythology folds naturally into everyday life here. Even the smell in the air of honeysuckle and incense mixed with cow manure and roasting spices betrays and confuses memory. I am gently reminded that I will never fully know this place, it will always keep something from the visitor.

Submarine at Scindia Ghat

If I told you that I passed a boat learning to fly or a monkeys that can talk to children I wouldn’t be entirely lying. There is so much rich storytelling material here that I was initially overwhelmed and even as I return to the river the more I continue to see, it seems to persist in its unfolding and I change to meet it, no longer phased by the pollution, poverty or beggars but with a resolve to address it my own home upon my return Aotearoa. On one walk along the river I find a submarine sat on the steps of the ghats and watch a sardu playing a convincing game of cricket with some local children, there is a stepwell called Manikanika Kund where pilgrims come to bathe that is a geometric dream that leads down to still pool which at night reflects the stars. Over on the river’s edge a temple sinks on its foundations and people bathe, cleansed by Mother Ganga.

Just along from Manikanika are the burning ghats with wooden logs stacked high in orderly towers. These are purchased by family who have brought their deceased loved one to the river for cremation and interring into the river. They walk in a procession along the road chanting and singing with the cloaked body raised upon their shoulders. This was a shock at first but after sitting on the steps watching the whole event unfold there is a very peaceful and natural aspect to this tradition. This process is the end point of reincarnation, death and rebirth, in the Hindu faith.

Leaving the ghats, there are endless chai stalls which is sweet and restorative for a weary pilgrim. I will often stand sipping the hot tea out of terracotta cups, which are smashed on the ground after use, next to shopkeepers who seem rooted like plants in their kiosks, growing too big for their container. A little further on there are holy men worshiping and chanting and slowly turning to stone, their faces covered in pigment and hair tied in a knot. I have become accustomed to the cows wandering the streets, lanes and alleyways around the city, I’m told they hold the gods in their bellies so I always give them some space as they wandering around unimpeded by the noise and pace of the city and you’ll see people tap them lightly as they pass.

This ancient city which is built on ancient cities whispers, ‘creation, destruction, creation, destruction’ endlessly as I weave through different areas of markets and temples. Hanuman, Shiva and Ganesha statues and shrines are everywhere and must come to life and coat themselves in vermillion paint in the night, which is the only way to explain the hurried paint job, always fresh but always quickly applied.

I have spent most of my time here filming the river from different ghats so I often find myself sitting on the painted steps that lead to different worlds beyond the river. The steps sit below castles and fortresses and fold out like origami to reveal that they are all one but with many different sides. There seems to be no wrong turn in Varanasi, just a different way to arrive at your destination. This adds to the many unexplainable yet somehow ordinary occurrences that life in Varanasi gifts you. This is a place where, as a tourist, you have to sit in the mystery and be carried by the flow of the traffic, the people and the rhythm of the river.

It is very hard to define this experience, being in amongst the chaos, the city seems to fold you into her disordered embrace and leads you, again, to the river. However, with the sun setting like a deep red bindi circle in the sky, it is perhaps necessary to speak in riddle or metaphor. And although it might seem mysterious, and I might be caught up in the allegory of this place, because of everything I’ve experienced in this enchanted place and for reasons I can’t explain, I now know what gold smells like.

Manikanika (Burning Ghats) from the river.

Check out the Asia New Zealand Residency programs here:

http://www.asianz.org.nz/about-us/our-programmes/grants-and-internships

Hut at Ganga Mahal Ghat

Getting Lost, sort of

As bats flutter and glide over Assi Ghat and the full moon rises through the filter of pollution and dust, which seems to be merged into the word “haze”, I’ve been thinking about how I no longer feel lost in this familiar place. Granted, it is only one small corner of Varanasi but it is familiar now, even certain street merchants and sadhus are familiar all interesting men with beautiful faces but rough hands and dusty toes.

Kids from a courtyard above the ghat kick a football over the edge and people below encourage each other to throw it back to them. The circus of nearly making it over the wall entertains the families gathered for the beginning of the Hanuman festival.

It is now normal to sit and watch the goings on of people down by the river, the people in bright coloured clothing alighting boats, a sound tech, checking the mic on a thrown together stage and watching teenagers who just hang out like they do the world over. Hanging back and not talking to girls while the girls wishing the boys would talk to them.

Also getting normal is men holding hands, linking pinky fingers or leaning on each other. This form of male affection is made by good friends and is normal behaviour in this religious and conservative state. They are normally sharing headphones plugged into their smart phones or just playing music out loud as they huddle in and enjoy the tinny rhythmic beat of Indian pop.

So before I forget the particular joy of being lost and finding it all very strange, let me elaborate.

Getting lost in Varanasi is a strange achievement because you are never really lost in this relatively small, ancient city; you may have just wandered too far down a different alley way than last time but there are very few dead ends here. This in a way, adds to the confusion. The labyrinthine layout of “streets” seems to be ingrained in the psyche of the locals but to a stranger it’s a vast matrix of interconnection that we don’t have the codex for.

And it should also be noted that you are never far from something which will captivate you so intensely that you may forget for a moment that you were trying to find your way out. Wandering, lost somewhere in a section of laneways in the Chowk region we happened upon a pristine courtyard, we spied through the gates a beautiful family temple which was a collection of tower spires painted in ash pink that stretched two, three and six meters into the sky. This was a momentary reprieve from the dark and dingy section of our journey.

There are very rarely directional or navigational signs and if there are they’ll be in Sanskrit which all looks like Sanskrit to me. However, way finding is made by remembering that in one area items like jewellery or brass blend slowly into spices and sarees. There is even an entire lane that supplies the area with all the milk curd they need for sweet treats, sitting in muslin sacks and brass trays on the cobbled walkway.

Looking on google maps isn’t much help either, though main road and lanes are mapped there are always paths and passes that are unmarked and it is a strange pleasure to look down at your phone and find that you are nowhere. You are outside of current technology and it always makes me smile knowing that there are people living their whole lives in lanes uncharted by google. This special lane where old men gathered to drink chai, endless chai, may have had the same action repeated uninterrupted by social media for centuries.

The lanes however small don’t seem to deter the casual motorcyclist. Always winding up smaller and smaller spaces these motorbike or scooter drivers will either yell “side” or just honk their horns. In the narrow walkways this can seem impossible but again like occupying a space that doesn’t exist people adapt. The smallest spaces are filled with life here and it makes the lonely streets of home seem like vast canyons to traverse from one side to another. There seems to be great community here, each family or group of families, often separated by caste live intergenerational lives among the ruins of temples, the too close cows and the constant passing by of tourist, but more often pilgrim and worshipper.

Great pride is taken in the presentation of shop fronts and entrances to homes even in the dark and dusty streets that are somewhere in the middle of destruction or construction, doorways are painted bright colours and shrines are adorned with fresh flowers and someone must have just left because the incense is still burning.

Temple, a street over from the river.

Temples of Durga

As I sit here with the paste and pigment of the Shiva tilak (ceremonial markings on forehead in the style of Shiva’s) drying on my forehead I am looking back over the 8 days and 9 temples, dedicated to the Goddess Durga, visited throughout Varanasi beginning on the first day of the Hindu New Year. Temples are the most common thing in Varanasi besides paan stalls and yet they always hold some mystique for me. They are in open spaces and crammed into alley ways or more correctly buildings and lanes are crammed up to them, so finding these places can be a mission but this all helps locate yourself when trying to figure out this city. As places of worship and pilgrimage I am drawn to them but as places of rules and protocols I am guarded.